Why is India still relying on foreign nations for fighter jet engines? That’s the bold question raised by Air Vice Marshal Suresh Singh (Retd), who recently urged India to end its dependency on international partners for engine development in the AMCA (Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft) program.

According to Singh, no foreign nation will ever share the core technology behind modern jet propulsion. The only path forward? Indigenous Jet Engine Development—powered by India’s engineers, scientists, and institutions.

At a time when the AMCA project is gaining global attention, Singh’s call for a domestically developed 120-kilonewton class engine has reignited a crucial debate: Can India build its own world-class fighter jet engine without external help?

In this article, we explore the challenges, breakthroughs, and strategic importance of building India’s first fully indigenous jet engine—and why this might be the most important step for the future of Indian defence.

The Harsh Reality Behind Foreign Jet Engine Technology

Why hasn’t India already secured cutting-edge jet engine technology from global aerospace leaders? The answer, according to Air Vice Marshal Suresh Singh (Retd), is brutally simple: “Nobody in the world is going to co-design, co-develop, or transfer core engine technology to you.”

These companies have spent decades and billions in R&D to build their proprietary propulsion systems. Sharing this intellectual property—even with trusted allies—would mean risking their global edge in aerospace dominance.

“Why should they lose revenue by giving you the edge?” Singh asked, underlining why relying on foreign jet engine programs is a strategic dead end.

This makes Indigenous Jet Engine Development not just a dream, but a necessity for India’s aerospace future. If India continues to depend on imports or joint ventures, it may always remain technologically behind in high-performance jet propulsion.

Instead, India must invest in building its own 120-kN class fighter jet engine through indigenous innovation, leveraging institutions like GTRE, HAL, DRDO, and academic partners to overcome the knowledge gap and build world-class capabilities.

Historical Lessons: Why Indigenous Jet Engine Development Is Achievable

Air Vice Marshal Suresh Singh (Retd) drew on powerful historical examples to show that innovation in jet propulsion is possible, even without external help. These lessons from early aerospace pioneers underline why India’s Indigenous Jet Engine Development journey is both realistic and essential.

Inspiration from Early Pioneers

Singh referenced Frank Whittle, the British inventor who patented the world’s first jet engine in 1930. Despite his visionary concept, Whittle struggled to find support and had to rely on personal loans to build his prototype. Yet his persistence eventually shaped the future of aviation.

Global Case Studies: Innovation Through Determination

While Whittle was laying the groundwork, Hans von Ohain in Germany, working with the Heinkel Corporation, developed a successful jet prototype by 1937, which took flight in 1939.

Singh also cited how General Electric in the United States reverse-engineered Whittle’s engine in just six months to create the A1 engine — a move that rapidly advanced America’s aerospace capabilities.

After World War II, Russia reverse-engineered British jet engines, resulting in the development of the VK-1 engine, which powered the legendary MiG-15.

These real-world examples prove that even starting from zero, nations can develop advanced jet engine technology—if they invest in R&D, talent, and national resolve.

The Challenges of Indigenous Jet Engine Development: A Long Road, But a Worthwhile One

Developing a jet engine is one of the most complex feats in aerospace engineering, and even the world’s best are not immune to failure. As Air Vice Marshal Suresh Singh (Retd) explained, “Engines are never perfect,” pointing out that leading manufacturers like Pratt & Whitney have experienced performance and reliability issues despite decades of experience and billions spent on turbofan development.

No Shortcuts: Perfection Isn’t the Goal—Progress Is

From turbine blade durability to combustion stability, every aspect of engine performance requires precision engineering, countless iterations, and live test cycles. India must be prepared for setbacks—but Singh argues that the path to self-reliance demands this perseverance.

Simulation Tools: Accelerating Indigenous Innovation

Thanks to modern aerothermal simulation tools, computational fluid dynamics (CFD), and AI-based predictive modelling, development timelines have drastically improved. Singh acknowledged that while these tools can’t eliminate all failure risks, they:

- Shorten prototyping phases

- Identify design flaws early

- Enable smarter, data-driven testing

“These technologies will fast-track our ability to deliver a reliable 120-kN-class indigenous engine,” Singh noted, reinforcing the case for investing in India’s Indigenous Jet Engine Development roadmap.

GTRE’s Role in Indigenous Jet Engine Development: Time for a Strategic Evolution

The Gas Turbine Research Establishment (GTRE) has been at the heart of India’s jet engine efforts for decades. While it made considerable strides through the Kaveri engine program, Air Vice Marshal Suresh Singh (Retd) was candid in his assessment: “You’ve had 40 years, and the results remain limited.”

Despite the setbacks, Singh acknowledged GTRE’s contribution to laying the foundation of India’s aero engine program. However, he urged the institution to evolve into a forward-looking, results-driven organisation that takes bold ownership of the nation’s future in Indigenous Jet Engine Development.

“The nation and media have been very kind to you,” Singh remarked. “Now is the time for GTRE to lead—not follow—in engine innovation.”

Singh emphasised that with access to modern tools, global benchmarking, and increasing funding, GTRE must shift gears:

- From R&D stagnation to breakthrough innovation

- From incremental tweaks to radical design leadership

- From closed-door labs to collaborative defence-tech ecosystems

With the right vision, GTRE could become India’s version of Rolls-Royce or GE Aerospace, leading the country into a new era of self-reliant defence propulsion systems.

Indigenous Jet Engine Development: India’s Roadmap to Aerospace Independence

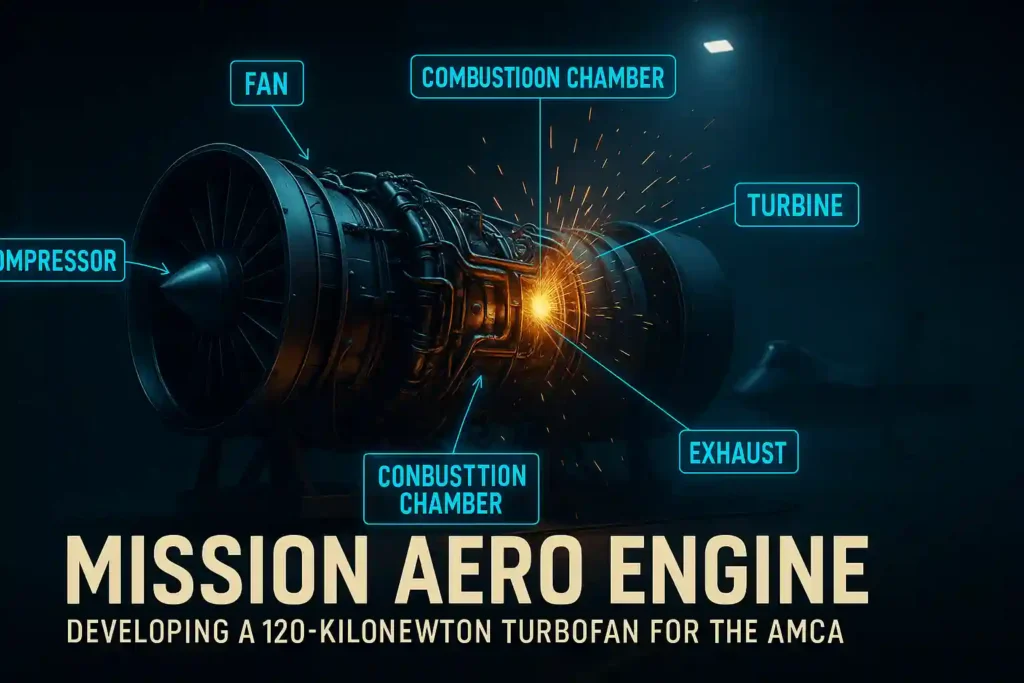

Mission Aero Engine: A Vision for the Future

As part of India’s strategic push for Indigenous Jet Engine Development, Air Vice Marshal Suresh Singh (Retd) proposed a bold initiative—Mission Aero Engine. This government-led program would aim to fully fund the development of a 120-kilonewton turbofan engine, initially for the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA), but scalable for:

- Military transport aircraft

- Naval fighter variants

- Commercial airliners like the Airbus A320 or Boeing 737

This initiative represents more than just an engine—it’s a statement of India’s aerospace self-reliance.

Unified Effort: Public & Private Sector Collaboration

Singh’s roadmap calls for the creation of a national aerospace consortium—a synergistic blend of India’s private aerospace companies, public-sector research labs, and startups/SMEs. His breakdown:

- Large private players to manage airframe, engine, and avionics systems

- DRDO & GTRE to provide R&D oversight and regulatory support

- SMEs & academic institutions to contribute to subsystem design, testing, and integration

Such a multi-tier collaboration model mirrors successful ecosystems seen in the U.S. and Europe, where government-backed innovation and private agility drive long-term results.

“This is not just about engines,” Singh emphasised, “it’s about building a self-sustaining, globally competitive aerospace ecosystem.”

A Risk-Sharing Consortium: Building India’s Engine the Global Way

To bring Mission Aero Engine to life, Air Vice Marshal Suresh Singh (Retd) advocated a globally proven model: a risk-and-reward-sharing consortium led by a fixed system integrator. Under this approach, each partner invests in the development phase and shares both technological gains and commercial success.

Learning from International Jet Engine Collaborations

Singh referenced global programs such as:

- V2500 Engine Program by International Aero Engines

- EJ200 Eurojet Consortium, which powers the Eurofighter Typhoon

These examples show how countries like Germany, the UK, and Italy successfully developed advanced engines through shared expertise, distributed costs, and integrated production.

“India must embrace this model if we’re serious about scaling Indigenous Jet Engine Development to global levels,” Singh asserted.

Government-Led, Industry-Powered

Singh stressed that while the Indian government must fully fund the program, execution should remain in the hands of a professional consortium, monitored directly by the Prime Minister’s Office.

Just like ISRO’s successful management of space programs, a centralised oversight mechanism would ensure:

- Accountability

- Timely decision-making

- Milestone-driven execution

- Long-term strategic continuity

The Urgent Need for Self-Reliance in Jet Engine Technology

In his final appeal, Air Vice Marshal Suresh Singh (Retd) delivered a powerful message:

“India cannot afford to wait another 40 years to build its jet engine.”

He warned that partial technology transfers, often touted as “99.9% reliable,” fall short when applied to critical propulsion systems. In jet engines, even a 0.1% failure can mean catastrophic consequences, risking both missions and lives.

Why Foreign Tech Isn’t Enough

Singh emphasised that Indigenous Jet Engine Development isn’t just a technical milestone — it’s a matter of national security. Reliance on foreign systems leaves India vulnerable to:

- Technology blackouts during conflicts

- Restricted upgrades or parts

- Inability to scale engine variants for future needs

A Call to Action for India’s Aerospace Ecosystem

He urged India’s defence and R&D bodies to rise to the challenge:

- DRDO – to lead R&D innovation

- GTRE – to evolve into a mission-driven design agency

- Ministry of Defence – to fund and fast-track Mission Aero Engine

The goal: to establish a world-class, self-sufficient aerospace sector, driven by indigenous expertise and global ambition.

The Role of Government in Indigenous Jet Engine Development

For Mission Aero Engine to succeed, Singh emphasised that the Indian government must take the lead, not just as a funder, but as a long-term strategic enabler of innovation.

Financial Backing with Strategic Oversight

He proposed full government funding for the Indigenous Jet Engine Development program, calling for:

- Dedicated budget allocations

- Timeline-driven milestones

- Cross-agency coordination

Most importantly, Singh urged that the program be overseen directly by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) — replicating the ISRO governance model, which has delivered multiple high-impact, indigenously developed technologies.

Accountability, Speed, and Execution

With PMO-level monitoring, India can ensure:

- Timely resource allocation

- Removal of bureaucratic hurdles

- Transparent vendor and consortium performance tracking

This high-level oversight is essential to make Mission Aero Engine a flagship initiative in India’s journey toward aerospace self-reliance.

The Need for a Unified National Effort

In his concluding message, Air Vice Marshal Suresh Singh (Retd) delivered a call that echoed beyond defence corridors:

“India must unify its scientific, industrial, and governmental will to succeed in Indigenous Jet Engine Development.”

He urged public institutions, private aerospace firms, and strategic ministries to come together, forming a seamless innovation ecosystem capable of designing and producing a world-class 120-kN turbofan engine for platforms like the AMCA.

Harnessing India’s Collective Strength

Singh believes that India can:

- Meet future defence needs through homegrown propulsion systems

- Reduce reliance on foreign jet engine suppliers

- Strengthen export potential in the global aerospace industry

This unified approach is not just about building an engine—it’s about cementing India’s place as a global technology leader in aerospace innovation.

Conclusion: The Time for Bold Action in Indigenous Jet Engine Development

Air Vice Marshal Suresh Singh’s final message was resolute — India cannot afford to wait another decade, let alone 40 more years, to develop its jet engine. The time to act is now.

With a growing talent base, rising R&D capacity, and proven aerospace manufacturing capabilities, India is fully equipped to drive Indigenous Jet Engine Development from blueprint to battlefield.

Key Takeaways:

- End reliance on foreign co-development deals that lack full technology transfer.

- Launch “Mission Aero Engine” as a fully government-funded national initiative.

- Build a 120-kN indigenous turbofan engine for AMCA, transport aircraft, and future platforms.

- Form a cross-sector aerospace consortium—uniting private firms, PSUs, DRDO, and academia.

- Establish India’s leadership in next-gen defence propulsion technologies.

By focusing on self-reliance, innovation, and strategic collaboration, India can not only power its skies but also shape the global jet engine landscape for decades to come.

The future of Indian aerospace doesn’t depend on foreign tech—it depends on India’s will to build.